This book and its theme are timely and poignant. We won’t stop waging wars. Some parts of the globe have long histories of it with competition for resources, land, water, trade and souls. Dwindling water supplies suggest more will come. We also won’t stop gardening – for food, shelter, beauty, solace – and this book is revealing on why. What gardening does for us – something that seems worth pondering and talking-up, as peace-fostering.

Obviously, disrupted food supplies, economic collapse, theft, looting and banditry mean that just being able to grow food for a family, amid conflict, as basic survival, is a key trigger.

Yet there are many other, similarly fundamental reasons. Ancestry, tradition, cultural practices, simple love of beauty or fragrance, a need for privacy, control, retreat: calm. And the cheering and mood-lifting activity of watching something grow, bear flowers, fruit…

This book by an English journalist (with delicious name and gardening parents) is a series of short interviews with people inside conflict zones familiar from TV or news-feed. These places include Iraq, Ukraine, Afghanistan, Gaza, Israel, the West Bank’s towns and settlements, as well as one foray to Arlington, the United States’ national war cemetery and meeting its head-gardener.

It makes for fascinating reading that I commend highly. I also admire Sydney City’s library system for buying it – perhaps a social agenda lies there, but undoubtedly a good one!

Snow aims at even-handedness, interviewing people ‘at war’ on both sides. Zig-zagging via police check points, translators, her driver putting prayer beads on, taking them off as religious pendulas swing back and forward.

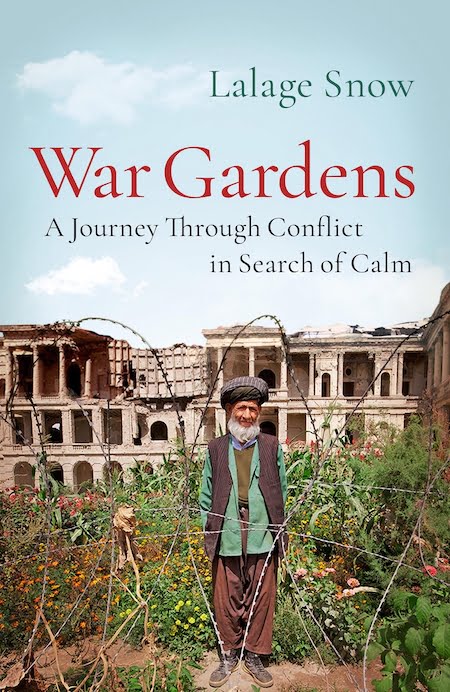

Her quotes from and photos of people she meets bring a personal, immediate spin to daily news-grabs, with human faces, mindsets, dilemmas and scenarios. These glimpses are fascinating and the opposite of corporate media reports which make places unreal and remote, always with third-person ‘comment’.

Snow’s not averse to commenting but presents many other voices. In some cases, as oral history, as gardeners open up and families and neighbours chip in. Subjects include soldiers and rebels: gun on back, spade or rose in hand! Some refuse to talk, be photographed: ‘No, my husband would not allow that’.

These poignant quotes give a flavour of the book and motivation for why people garden:

‘The first thing most people did was plant a tree – for shade, kindling and fruit, obviously, but more than that. It is about putting down roots. It’s part of the Afghan psychology’ (Jolyan Leslie, who is leading redesign and reconstruction of some key Mughal gardens in Afghanistan).

‘Everyone needs a garden. This is our soil. When you work with it, things grow. It’s nature, life. I am a poor man, sometimes my family and I only eat once a day, but I can live without food; I couldn’t live without seeing green leaves and flowers: they come from heaven. Each one is a symbol of paradise’ (Mohammed Kabir, municipal gardener, tending the Afghan Army’s Kabul garden).

‘I like to be here all the time’ (Huda, Gazan gardener and grandmother. From her garden) not only can she feed the 3 generations (some 56 members) of her family with fresh produce, she can also preserve and pickle the surplus as well as making olive oil. In an ideal world she would sell this too. As an illiterate woman now empowered as the breadwinning matriarch, she is proud of this achievement.

‘I had a friend who was teaching psychology at a university and she asked me, what do you do with Freud in the garden? Jung in the garden? Nietzsche in the garden? I knew a bit about philosophy and so I helped her develop a whole project about gardening therapy. Gardening is one of the most effective ways of re-earthing yourself, being calm and not a fanatic. I live in a part of the world where, let’s face it, people could do with a lot of good hash or a garden, and it’s cheaper to garden. And legal’ (Mikhael, Sderodt, Israeli kibbutz).

‘I don’t have an outside garden, but I keep over 30 plants on my balcony. In the spring I grow green onions and, in the summer green peppers and tomatoes, which my granddaughter enjoys looking after with me. I like seeing my tomatoes against the clear sky, but I suppose I will have to put tape up on the windows if the explosions and fighting continues’ (Alexander, 22-year occupant of a Donetsk apartment, Ukraine).

‘This time last year I was beginning to preserve and pickle everything I had grown for the winter. Now look… (devastation). This is usually just a nice, quiet suburb of Slavyansk, and this is everything I have ever worked for, there’s nothing left. Not even the vegetable preserves. My son has told me not to garden because of the mines’ (Alexandra, Semonyovka, Ukraine, who hid underground for a month during shelling, with nowhere else to go).

‘God created us from the soil, we eat from it and bury our dead in it. I can’t describe the link between man and land more clearly than that’ (Fayez Taneeb, Palestinian permaculture farmer, West Bank, Israel).

‘I learned it from my own mother when I was only five, so I understand that when a child plants something, they feel it. Some of the children here have suffered huge amounts of violence and trauma, but when I watch them planting or playing with soil, I know that they feel it healing them’ (Zleika, Palestinian teacher, H2 (Israeli-military-controlled Hebron).

‘I had a friend in the army, an officer. He was like a brother to me. He was killed, fighting, about a year and a half ago. I was so sad. I… I couldn’t sleep for grief. I tried to garden to forget him but, in the end, I planted flowers to remember him and when one grew, it was like I had a new friend. So what can I say, my flowers are good friends to me’ (Hamidullah, teenage student, Parwan, Afghanistan).

War Gardens – a journey through conflict in search of calm, Lalage Snow, Quercus Editions Limited, 2018, ISBN 9781787470682