Most people serious about gardening will have a favourite part of their local city’s botanical garden. Perennial borders, sweeping lawns, pools, lakes, conservatories and grottos – botanic gardens the world over are jam-packed with so many areas of interest that choosing only one favourite area is difficult. As much as I love watching the perennial border in the Royal Botanic Gardens here in Melbourne change with the seasons, my favourite part of the gardens is much more austere. I should confess here that I am a treeophile. I simply love trees. Give me a gnarled, ancient tree over a showy perennial border any day of the week – pretty herbaceous perennials are nought but horticultural tarts compared with the regal majesty of a tree that has seemingly been there forever.

My favourite part of the RBG Melbourne is the Separation Tree, a large River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) that predates the gardens themselves by at least a couple of hundred years. So-called because it was the tree under which Victoria’s early colonists gathered to celebrate the separation of Victoria from New South Wales in the 1850s, the Separation Tree is older than Melbourne or even Australia itself. It is tragic that in 2010 a vandal saw it fit to take to the Separation Tree with an axe in a concerted effort to ringbark it, no doubt with the express purpose of killing the tree. After a year and a half of intense management the tree is looking remarkably well considering the extent of its injuries, and some interesting horticultural trickery is being used in an effort to save this iconic tree from what would otherwise be a certain death.

For any plant to grow it needs water, light and nutrients. The water used in photosynthesis is taken up by plant roots and eventually ends up in leaves, where it plays a crucial part in converting carbon dioxide into carbohydrates before releasing oxygen. The carbohydrates manufactured in the leaves during photosynthesis are then carried down the cambium of trees to the roots where they play a vital role in forming new roots that help to sustain the tree. The cambium is the live layer of tissue found underneath a tree’s bark and is crucial in transporting carbohydrates. Ringbarking severs the cambium, effectively stopping these carbohydrates from getting to the roots, and so it is that a ringbarked tree will eventually die.

Fortunately, the Separation Tree vandal did not manage to sever all of the cambium with their frenzied hacking. A little live cambium still remains on the tree, after intensive management by RBG staff I might add, but nowhere near enough for the tree to survive on its own. The initial response to the attack by the RBG staff was to wrap the tree’s extensive wound in hessian, keeping it moist and the tree well watered, and wait to see if any of the remaining parts of the cambium would survive on their own. Regardless of how much survived after the attack, additional intervention was going to be required if the tree was to survive in the long term. The unusual and impressive technique of bridge grafting was then employed in an attempt to put the Separation Tree back together again.

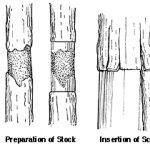

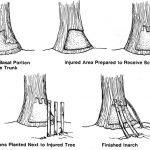

Bridge grafting is a grafting technique that is usually only employed in situations where, through disease, predation or vandalism, a tree has been ringbarked. It attempts to ‘bridge the gap,’ as it were, above and below the ringbarked area, uniting the damaged cambium and once again allowing nutrients to flow and the tree to survive. Branches from the damaged tree can be used to form the bridge, or new sapling trees can be planted near the base of the tree and an approach graft attempted to achieve the same outcome. Both methods have the same aim and differ only in the method of execution – bridging the gap between the cambium void is the ultimate goal. Both the bridge graft and approach graft methods have been used on the Separation Tree in an attempt that one (or both) of the methods will achieve a successful reunion of the cambium. As it’s a year and half since the attack took place, the tree is looking remarkably resilient. One of the first signs of tree stress is a thinning canopy, but the Separation Tree’s canopy still looks quite full despite its extensive injuries. The next six to twelve months will be crucial in determining if the tree is going to survive, but rest assured the RBG staff and many other national and international experts are monitoring the tree closely, giving it all the help they can. With the bridge grafting techniques already applied to the tree, and ongoing TLC by some of the countries leading arborists, there is still reason to remain optimistic for the tree’s future. With a little luck and a lot of horticultural ingenuity, here’s hoping the severed halves of the Separation Tree can be united once more.

Happy gardening.

[* Bridge & approach grafting diagrams from: Bir R.E., Bilderbeck T.E. and Ranney T.G. Budding and Grafting Nursery Crop Plants, NC Cooperative Extension]#gallery-1 {margin: auto;}#gallery-1 .gallery-item {float: left;margin-top: 10px;text-align: center;width: 33%;}#gallery-1 img {border: 2px solid #cfcfcf;}#gallery-1 .gallery-caption {margin-left: 0;}/* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */ Lush perennial border at Melbourne RBG

Lush perennial border at Melbourne RBG Grafting repairs to the Separation Tree

Grafting repairs to the Separation Tree Repairing the severed cambium with grafts

Repairing the severed cambium with grafts Bridge grafting technique *

Bridge grafting technique * Approach, or inarch grafting technique *

Approach, or inarch grafting technique * The Separation Tree with a healthy canopy (Photo James Beattie 2012)

The Separation Tree with a healthy canopy (Photo James Beattie 2012)