“Neither Art nor Science are very materially remunerative professions but very soul-satisfying both.” OLIVE PINK TO WILLIAM CROWTHER, 1935. A fiercely independent woman ahead of her time, Olive Pink is best known for her staunch support of the Aboriginal People of Central Australia, which is illustrated in this edited extract of the book Olive Pink: Artist, Activist and Gardener

CHAPTER 7 Anthropology, art and travels in Central Australia

With her growing interest in Aboriginal culture and welfare, Olive Pink took a few hours’ leave from her job each week and attended anthropology lectures at the University of Sydney. As she had not matriculated she could not do a full degree but she was able to enrol in all the subjects related to anthropology and her studies would allow her to carry out anthropological work in Central Australia. That was her ultimate aim at this time.

In 1932, at the Sydney meeting of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science (ANZAAS), Olive gave a paper titled ‘A few notes on the uses to which the Arunda and Arabanna tribes of Central Australia put their indigenous flora’. The abstract states that it was ‘illustrated with water-colour drawings made at various camps between Port Augusta and Darwin, and then Alice Springs and Hermannsburg’ and that it ‘dealt with the food, medicinal and ritual uses to which plants and flowers are put by Australian aborigines’. The abstract also noted that the paper examined how vital ‘the indigenous flora is to these people – nutritionally, medicinally and ritually. And how detrimental to their physical (and spiritual) well-being is the restriction of their freedom to collect and hunt over their local group’s country and perform their ceremonies at the ritual sites in it – since these can be performed by them nowhere else.’1

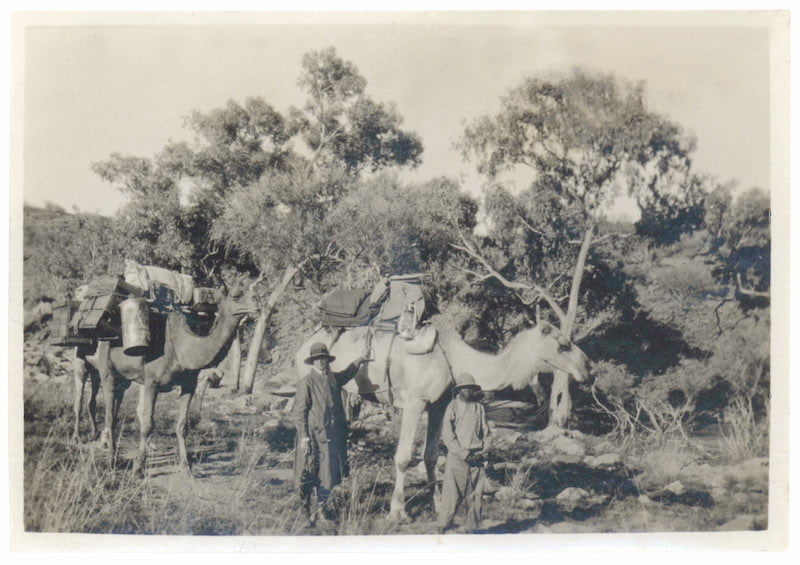

In this paper Olive brought together her great passions: art, Aboriginal welfare, flowers and plant conservation. A delegate to the ANZAAS meeting praised her dedication to her research, describing her trip in 1930: ‘She rolled up her swag and travelled alone from Port Augusta to Darwin. She played a lone hand, and therefore is to be heartily congratulated for the valuable data she secured.’2 Olive explained that her original aim during the trip was to obtain the Aboriginal names for the plants she painted on her journey and that the information she gathered about how the plants were used was incidental but fascinating, and led to her writing the paper. ‘But the Aborigines seemed as interested in volunteering the information as one was in hearing it – (as to the economic, medicinal and even ceremonial uses to which some of the specimens painted and collected are put).’3 She documented the uses of several plants, and one example describes how the Aboriginal people used one of Olive’s favourite flowers, the native bluebell, Wahlenbergia gracilis. She wrote that her Aboriginal friend told her that the seeds were ground into flour and:

he went on to add that they sometimes strip the blossoms and leaves and boil them! ‘All same cabbage – Very sweet.’ That remark was almost Too Much for one’s aesthetic feelings. The elusive beauty of rare, but large clusters of tall Blue Bell plants (one group I saw were at least from 3 to 4 ft high, bordering part of a creek bed in Central Australia) with its misty blue – was something to be remembered with joy. But for such loveliness to be looked on as (potential) cabbage was – one felt, rather overdoing the utilitarian idea.4

After passing her anthropology examinations, Olive retired from the Railways drawing office in 1933 with a small pension. She was desperate to return to Central Australia but she had very little money to travel there independently. To qualify for research grants from the Australian National Research Council to carry out anthropological fieldwork she had to write a thesis to finalise her qualification as an anthropologist. Fortunately she was able to delay her retirement until after her paid annual leave so that she could use her last entitlement to an employee rail pass. She travelled to Central Australia to do the necessary fieldwork research for her thesis, which was to describe the ritual ceremonies she had first learned about on her trip in 1930.

On her return to Sydney, with much effort Olive submitted her thesis. Now recognised as an anthropologist, she received an Australian National Research Council grant of £300 in 1933 and spent a year camped in the desert doing research on the Arrernte and Warlpiri people. Another grant in 1936–37 allowed her to do more research among the Warlpiri. Throughout these years she continued her botanical sketching.

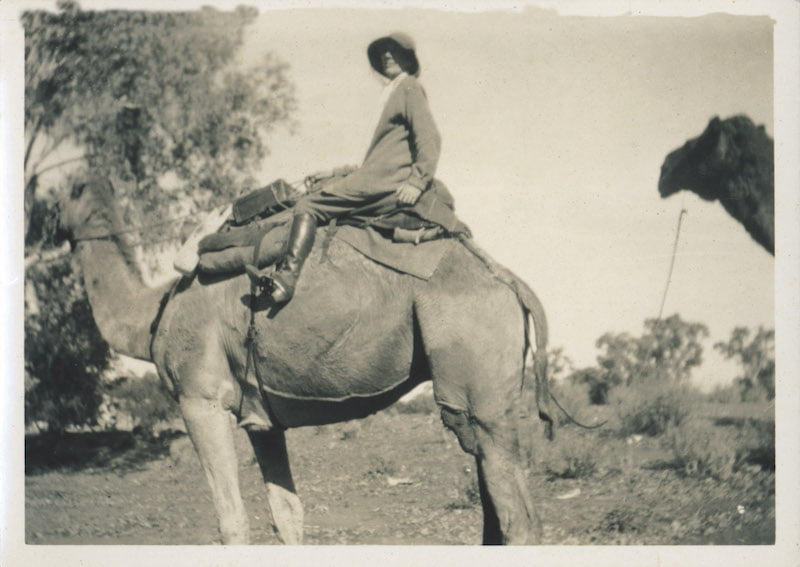

Olive Pink in Central Australia

Olive was passionate about the creation of a reserve for the Warlpiri people where they could live without interference from missionaries, away from white laws and customs, and safe from sexual exploitation by whites. In their own secular reserve they would be able to live in a traditional manner. Olive’s outspoken views and her antagonism towards missionaries were considered controversial and were not generally supported by the anthropological fraternity.

At this time, in 1935, her financial situation was difficult, as she wrote to her childhood friend, Dr William Crowther: ‘My private income is microscopic and the Grant I receive is very small also. Neither Art nor Science are very materially remunerative professions but very soul-satisfying both (which is the all-important thing.)’5

Olive Pink delivers her paper at the ANZAAS congress

Olive delivered further papers on Aboriginal culture at the ANZAAS congresses in 1935, 1939 and 1946, and wrote articles for Oceania in 1933 and 1936, as well as several articles for other magazines and newspapers. One entitled ‘My Bush Sundial, in the Macdonnell Range [sic], Central Australia’6 she signed with the pseudonym ‘Truganini’. It was the name of the woman believed to be the last person of unmixed Aboriginal ancestry to live in Tasmania and it reflected both Olive’s concern for Aboriginal welfare and her desire to identify with her birthplace.

The article describes particular arid-lands flowering plants as a sundial. She documents flowers that open at certain times of the day as a way to tell the time by colour, which she calls the ‘Stone-Age man’s watch’. She describes the colours of each flower and the time of day they open as a regular cycle or coloured sundial. The ‘purples’ and one orange flower are all up at sunrise, a blue flower opens between ten o’clock and two. An apricot flower opens in the afternoon, followed by a pea-flower of ‘sunset shades’ and a pale yellow flower at sunset, and then a greenish-cream nicotiana overnight. She wrote: ‘By sunrise the Purples will be up. So my dial is complete.’ This interest in colour is part of her artistic nature, and her letters and notebooks contain many references to colour in plants and in the landscape. It also shows her close observation of nature and her interest in Indigenous methods of measuring time.

During the 1930s Olive made friends with the artist Albert Namatjira. They often met and talked about art, and she bought two of his early paintings, which were among her favourite possessions. In a letter from 2 October 1959 to William Crowther, who was a trustee of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, she asked his advice about how to ensure that her paintings would go to the museum when she died:

I do not know if I showed you two paintings, by Albert Namatjira, that I own – when I was last in Hobart? I bought them at Hermannsburg Mission from the Pastor, and Albert, in 1936 or 37. And I would not exchange them for any of his later work! Those I have have a spiritual quality that his later work lacked. And a great simplicity of treatment.

(There are also on the back of each – a trial attempt of another scene!) When I bought them, Albert said, with a smile, ‘You are getting two on each, for your money!!!’ Those earliest paintings of his were not signed. Then he signed them ‘Albert’, (only), and when he had ‘arrived’ – signed ‘Albert Namatjira’ – (as you would have seen).

When I decided to ‘Will’ them to the Hobart Art Gallery (with two water-colours by Harold Southern), I showed his two to Albert and asked him would he care to sign the back with both his original signature, and his later one? That he did – in his usual pleasant way. It would have been wrong to get him to sign it on the front as it was not done (any signature) at the time I bought them. He was only ‘a beginner’ then. But a brilliant one, (in his simplicity of treatment)…(But I want to keep them here while I am alive – as I love them. So I don’t want to submit them, now.)

Olive described the two Harold Southern paintings she offered to the museum as, ‘One water-colour is of daffodils. And everyone who sees them exclaims at their beauty: “the very spirit of daffodils”! The other is of “Paper-bark trees on the banks of the Swan River, Perth.” (W.A.) and is, to me, very beautiful too. From boyhood, Harold was a great friend of mine. He had a very brilliant brain:- both for artistic and scientific work.’7

Olive Pink’s image of children at the waterhole

Olive was a keen photographer and used her camera to document her anthropological work. While camping in the MacDonnell Ranges and preparing for an expedition to Mount Gillen with her Aboriginal guide she described the things she took with her: ‘and [I] looked in the bag to see if “tucker”, pencil and paper, brandy, little gadgets for snake-bite, and Kodak, were all there, took the water-bag and started out, confidently’.8

She did not like having her photograph taken, particularly later in life, and she professed not to like having photographs on display. She did, however, display a photograph of Harold Southern in her room. She also kept photographs of her family, friends, tents, huts, houses and gardens with descriptive notes written on the back, which help to tell her life story.

Olive Pink on a research trip in Central Australia

Olive’s research trips in Central Australia during the 1930s gave her a much better understanding of how the Indigenous people lived there. Her desert camps and the friendships with people she met on her trips provided Olive with an enormous amount of data to analyse. She was exhausted by the heat and humidity and in 1937 decided to leave Alice Springs for Sydney, where she could more comfortably concentrate on writing up her research.

This is an edited extract from Olive Pink by Gillian Ward, published by Hardie Grant Books, and available in stores throughout Australia.