Having never been to Japan I was immune to the romance of the Japanese Red Pine, Pinus densiflora. Until, that is, I saw the recent Katsushika Hokusai exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria.

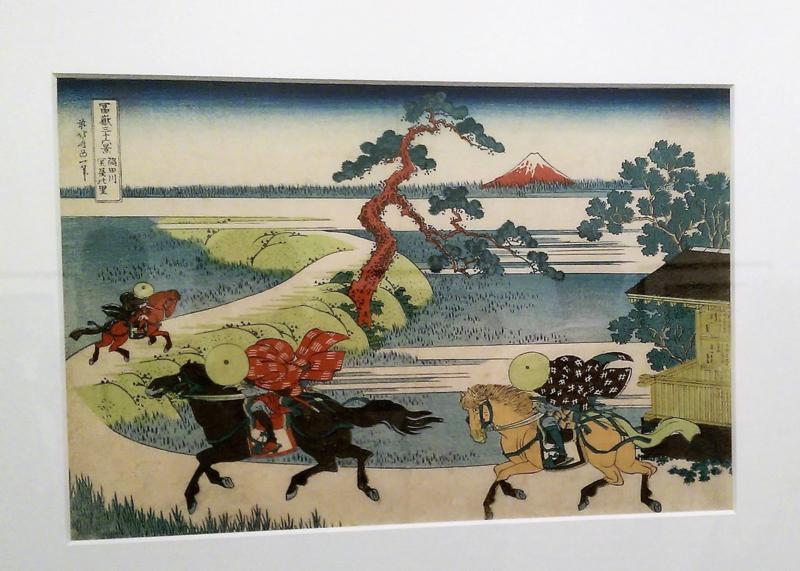

Sure I saw The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 50 views of Mt Fuji (including one at the rear of ‘The Wave’, and in background of the one I’ve featured above), and even the Giant Butterbur (Petasites japonicus) in one of Hokusai’s manga books. All very interesting but what grabbed my attention was a red-barked tree, clearly a pine, and clearly something rivaling the Mediterranean Stone Pine (Pinus pinea) in its striking form.

So I thought I’d look for one in our own botanic garden. As luck and planning would have it, we do grow a cultivar called ‘Pygmy’, in our approximately appropriately called Ponderosa bed. (The garden bed includes an old Pinus ponderosa, another pine species (Pinus mugo), a couple of She-Oaks, and some mat-rushes and grasses.)

The Ponderosa bed is just inside The Ian Potter Foundation Children’s Garden and, apart from the Ponderosa Pine, planted since 2004. This (dwarf) Japanese Red Pine is one of the original plantings (although a little stressed at the moment the new growth looks healthy enough).

The Japanese Red Pine also occurs naturally in North and South Korea, where it is, naturally, called the Korean Red Pine. Those growing in North Korea and nearby Russia are sometimes considered different enough to be given another botanical name, Pinus funebris.

In both Japan and Korea, Red Pines cover large areas in pure stands. As in Japan, the tree has strong cultural importance in Korea. Not only is it mentioned in South Korea’s national anthem, it turns out to be the most frequently mentioned species mentioned in ‘tree-related proverbs’ and folk stories.

Where the species extends into China there have also been some taxonomic interventions (i.e. new names) but these are not generally accepted.

Japanese/Korean Red Pine is closely related to the also more commonly planted Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris), a European-Asian tree planted in a couple of spots on the eastern side of the Melbourne Gardens. Scots Pine has shorter, broader and waxy blue needles.

Both are important timber trees, with the Red Pine used mostly for paper these days, although also for underground mining supports and railway sleepers.

It is the bark, though, that sets it apart from most other pines, although not so much Scots Pine. The flaky outer layer is red, or orange-red, particularly on the upper parts of the trunk. Hokusai seems to have exaggerated the colour a little in his woodcuts but in the right light I’m sure the bark is bolder in colour than what I’ve photographed here.

In Japan the species is very popular in horticulture, with up to 100 cultivars available. You’ll find it (I’m told) around shrines and places, as well as in bonsai. Traditional medicines make use of the needles and pollen.

I see ‘Pygmy’ described (incidentally as a cultivar of a form of Pinus densiflora called umbraculifera) as upright, globose (rounded) and ‘very dwarf’. I’m not sure any of this terminology is contemporary but clearly this is a small form of the tree. Indeed the tree is rarely grown in Australia except in bonsai.

The form umbraculifera is treated as a cultivar name, ‘Umbraculifera’, by Roger Spencer in his Horticultural Flora of South-eastern Australia. Its name refers to the flattened, umbrella-like crown of this variant. I’ll keep an eye out on our specimen to see if it matures into an umbrella or a sphere.

Or maybe something far more eccentric and artistic, like the specimen portrayed by Hokusai. I wonder what the children would prefer?