After a couple of recent visits to Norfolk Island, a sublime place sitting like an emerald jewel in the glistening, turquoise South Pacific 1,200 or so kilometres east of Australia, I came away with much gardening and sustainable food for thought. An island community such as Norfolk operates day-to-day with the sort of restrictions us mainland gardeners cannot even begin to imagine – most materials are brought in at great cost by sea and the import of plant materials is highly restricted. A home or market gardener on Norfolk Island is more likely to actively adopt sustainable practices for purely pragmatic reasons than by some feel-good choice; it’s the only sensible way to have a great garden or produce quality crops.

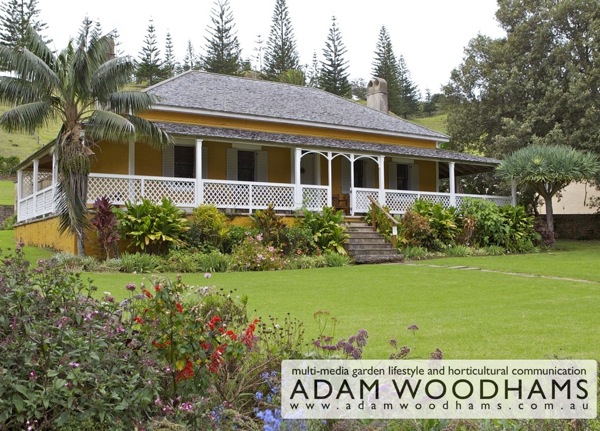

Magnificent Norkfolk Island home and garden

I was very taken by this as it in many respects proves much that I’ve been saying for years – sustainability is actually easy, not some challenging and complex task.

My garden visits were often quite comical. I’d be flapping my arms about excitedly declaring “Wow… that’s just amazing that you do that!” as the gardener or farmer would carefully inch away with that back-away-from-the-crazy-man look on their faces, shrugging, while in a slightly bemused fashion asking “why wouldn’t you?” And that perhaps sums up the sustainable scenario as I see it – why wouldn’t you?

Reuse and recycling are huge on the island. Perhaps the most prominent example of this dates back to when the Pitcairn Islanders – the descendants of the famous Bounty mutineers who were ‘given’ the island by Queen Victoria – arrived in 1856. They promptly dismantled, or ‘quarried’ as it’s euphemistically described, many of the prison buildings left abandoned from the previous penal settlement to use for building their own homes and for public works. As much as this may seem almost sacrilegious to our modern sensibilities it was a no-brainer for them – why quarry and carve new building materials from virgin earth when expertly crafted supplies were just sitting there waiting? Even today many homes have a small stock-pile of ‘convict stone’, whose origins are lost in time, waiting for reuse around the garden.

Marsden mats

My favourite reuse is however a much more recent one. Like many remote islands Norfolk Island only gained its airport thanks to World War II, as it was seen as a potentially valuable refuelling and communications point. In 1942 an airstrip was laid down and a radar base established. As was often the way with these remote strips, a material called Marsden or Marston mats was used for the runway. These ‘mats’ are large perforated steel sheets each measuring 3m x 30cm and weighing around 30 kilos. They quickly interlink and, with a bulldozer or two for levelling and enough manpower for the laying an airstrip, can be created overnight. As the mats have a high manganese content they are highly resistant to rust meaning that, you guessed it, many of them are still there on the island today good as new. You see these Marston mats in the oddest yet most ingenious of places – fencing, pig-sties, chicken coops or, as I saw, used as reinforcing panels in a rendered concrete chimney. I reckon used well they’d even make great garden art!

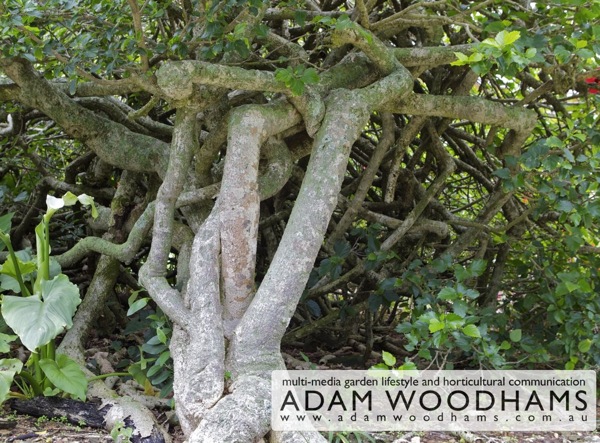

Norfolk Island hibiscus

As a gardener however what struck me the most was the heritage of the plants on the island, I won’t even go into the island’s unique native flora, I’ll save that for another time. I’m talking about the imported productive and ornamental species. Every wave of settlers on Norfolk Island have brought with them plants that they value. When Lieutenant Philip Gidley King (later to be Governor of NSW) commandant of the first Norfolk Island colony in 1788 pushed through the then dense coastal vegetation to explore further up a small river near the first settlement, his team encountered small plantations of a banana variety. Far from native, these bananas, likely plantains, had been originally brought to the island and grown by the first known settlers – the Polynesians – well over 300 years earlier. These same varieties are still grown on the Island today, with some locals calling them ‘Sydney’ bananas, probably because they were found along the river feeding the town of the first colony. The town, today known as Kingston, was originally called Sydney well before Sydney Cove on the mainland was named as such.

Norfolk Island Garden

Today in private and public gardens examples exist of plants that mainland gardeners would describe as ‘heirloom’ varieties. I would hazard a guess and say that there are ornamental and productive varieties on the Island that have a lineage straight back to the first boat that came ashore with the First Fleet. In fact I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the Island is an unwitting reservoir of these old forms. I heard tales of first settlement gardens, dating back to the 1790s, gone wild with the imported plants having acclimatised. I don’t doubt this as plants such as divinely fragrant Rugosa roses pop their heads up in the oddest of places and you encounter curious things such as seeing what appears to be the same flower form of Hippeastrum in garden after garden. At first I put this down to a chronic case of over-sharing one variety then it struck me – it’s more likely that the form is a very old one or that the cultivars on the Island have over time reverted back to a more pure original or natural form.

A story of one plant however stuck with me the most, probably because I’m a wee bit of a closet history train-spotter. The plant was a humble red Hawaiian-style hibiscus. This plant at once gave me goose-bumps for its heritage and a salient reminder of the responsibility of being a garden owner or designer.

We tend, as designers and gardeners, to consider trees as the great survivors of landscapes, standing like sentinels, resolutely, possibly for centuries (assuming they survive urban sprawl and today’s tree-phobics). We don’t generally give much thought to the smaller plants, the shrubs, the annuals, the veggies; they’re seen as more transient, more ephemeral. This one hibiscus however gave me a wake-up-call on that point.

Magnificent Norfolk Island hibiscus

In today’s World Heritage-listed Kingston, technically the capital of Norfolk Island, is a breathtaking stretch of pre-1850s streetscape called Quality Row. It’s a stunningly well-preserved collection of Colonial Georgian-style buildings with, in many cases, gardens that suit the period of the architecture. Number 10 Quality Row is the finest example of these buildings and gardens open to the public.

If walking down Quality Row is like looking through a window on history, to open the gate and step into the grounds of number 10 is to step back in time. In one street-side corner of the garden is a large red hibiscus. Nothing sets it aside as unusual, it’s around 2m by 2m and flowering beautifully, but when you peek beneath the canopy you find a network of short thick trunks that tell you this plant is no newcomer. Photographs from as early as 1890 show this hibiscus rambling halfway across the yard, to have reached the size in the photo it must have already been at least 20-years old. So here in one small plant we have living garden heritage that’s likely approaching 150-years of age. It has been shredded back to stumps by countless cyclones, scorched by the torching of adjoining buildings and silently borne witness to the births and passing of numerous residents. And gardeners…

So next time you’re putting a plant in your garden, even if it is just a humble little old hibiscus, perhaps it’s worth mulling over for a moment or two just who it is that’s ephemeral in the landscape.

For more information on Norfolk Island visit www.norfolkisland.com.au or drop by my webpage www.adamwoodhams.com.au