In a previous life, I worked as a programmer. My world was technology. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve found my way into the natural world. The change was sudden and overwhelming, and I made many mental leaps to reconcile being a ‘plants person’ as well as a ‘tech person’.

But looking around now, I see increasingly that the gap between technology and nature, at least the one I believed in, is closing.

When I told my nerdy friends my fingers were turning green, they sent a deluge of links to technology things related to the garden. It went beyond an automated retic system, though that has changed my life as well. I’m talking about very cool gadgets that not only make life easier for enthusiasts with ever-busy schedules, but also make gardening possible for people who would simply find it too difficult to get started otherwise.

Making gardening easy (and possible)

Modern consumer products, like the Parrot Flower Power allow gardeners to automate the menial task of remembering when and how much water, fertiliser, heat and sunlight to give their plants.

Source: Parrot Flower Power

Already very nifty, but this basic functionality can be extended even further with affordable electronic ingredients, such as the Arduino, Raspberry Pi and software services, to create a ‘smart garden’ that takes care of its own needs. Imagine, for example, a garden that could read the weather report from BOM and automatically adjust when and how much to water itself based on ambient temperature, humidity and moisture levels in the soil. Or a drone or robot that could recognise and harvest ripe fruit.

Using a drone to sweep the leaves in your backyard.

Among the people I know who would like to garden more, the two biggest complaints I hear are lack of outdoor garden space and lack of time. Here’s where indoor growing technology can help. I don’t mean complicated hydroponic setups or large scale industrial production shelves (though these are very clever too!), but aesthetically pleasing self-contained units that make naturalism possible for people living in dense urban areas or in one of the many, many garden-scant properties developed over the last ten years.

CounterCrop is a technology enhanced indoor plant growing unit.

These units are designed to give plants the light, space and nutrients they need to provide the household with a year-round supply of edibles. The CounterCrop, for instance, builds on the previous generation’s standard indoor plant light. It regulates both water and light, cutting back on mess and clutter, and requiring little human intervention.

Source: grovelabs.io

More upmarket is the Grove Ecosystem, adding aquaponics to the mix. Again, with light and water looked after, all you need is enough space for what is effectively a shelf, along with a supply of electricity and an internet connection.

Though the mileage will vary in how technology like this fits into your life, or on your kitchen counter, it certainly lowers the barriers to entry for people bound to apartments and dark houses, or for those with unforgiving schedules. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say these innovations swap the effort barrier for a money barrier that fits the budget of consumers in the high-technology demographic.

Automatic reticulation has come a long way. With the ‘too hard’ parts taken care of for both entry-level and seasoned gardeners alike, new technology can definitely alter the day-to-day routines for keeping plants and growing food.

Securing our food for the future

VertiCrop claims to produce up to 20 times more yield than field crops and using only 8% of the water typically required for soil farming.

Speaking of food, the future of our food security is a hot topic these days, and technology doesn’t shy away from trying to solve the problem – or at least try to alleviate its severity. LED bulbs and solutions like the VertiCrop can revolutionise large scale food production for many types of crop, reducing the environmental footprint and impracticalities effected by rural agricultural sprawls.

Vertical farming makes food production possible in high-density urban areas. Imagine your salad produced in thriving conditions in an inner city warehouse. Even better is to imagine factory production no longer being synonymous with artificial and unhealthy.

The futurist in me can’t help but picture in terror a world where large expanses of natural country have been replaced by forests of factories. But I like to think we’d never let it get to that. Plants would still be grown outdoors, there would still be natural habitats, and we could ensure all this whilst being able to feed everyone.

Source: Svalbard Global Seed Vault

Even more reassuring is the ‘Doomsday Seed Vault’, a secure seed storage facility built inside a mountain in Svalbard, between mainland Norway and the North Pole. It’s the world’s largest collection of crop diversity, currently holding over 860,000 samples, stored in sealed packages in a highly controlled climate below freezing temperature. Compared to self-piloting drones and robots, the refrigeration technology in the seed vault doesn’t seem so high tech, but the vault does provide us with a fail-safe for the future of our food.

In late 2015, mankind made its first withdrawal from the seed vault, spurred by the devastation from the Syrian crisis. The seeds withdrawn from Svalbard replaced the stock in a regional seed bank that provides crop supplies to its local Middle Eastern region.

When technology learns from gardens

Humans have been effectively ‘gardening’ for over 12,000 years, and developing technology (though primitive at first) to make it easier to reap the benefits. Nature inspires the technology we develop for ourselves too, now in more complex and interesting ways than ever before. Synthetic solar cell leaves, for instance, mimic the way real leaves work. But instead of the energy produced going to fuel plant growth, it can be used to power cars, computers and electric lights. Even indoor lights used to grow plants – doesn’t that blow your mind?

Moss table by Biophotovoltaics

We’re also seeing a fusion of technology and nature, such as in biophotovoltaic moss. The moss performs its natural photosynthesis and releases biological compounds into the soil. These compounds are then broken down by soil bacteria, with the biochemical byproducts used in electrochemical reactions, and the resultant electrical energy harnessed for human use.

Source: Electronic Plants

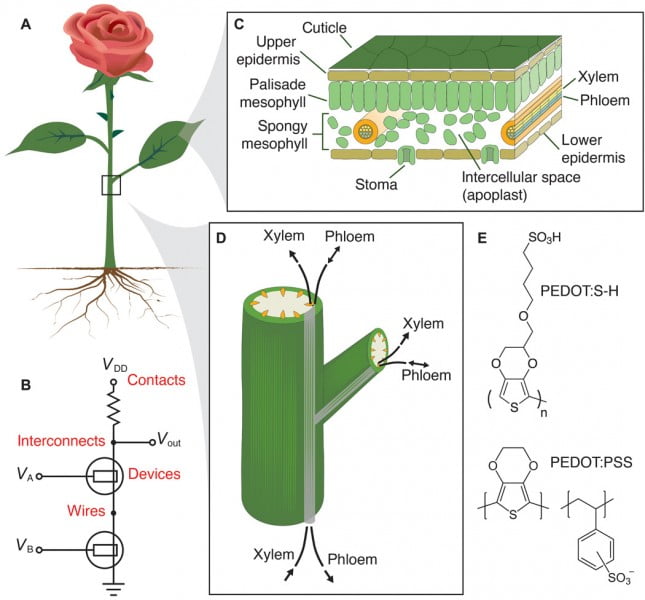

Finally, in more recent news are the famed ‘cyborg roses’, which take up polymers through the natural process of transpiration, and form wires within the vascular network of the plant. Using sensors, signals and interpreters, similar to the smart electronics we talked about before, the plant’s needs and observations can be translated into a more widely understood human language. This type of technology isn’t new – Mother Nature has already invented plants that tell humans if the air is high in ozone – but being able to harness these features in plants of our choosing gives us far more control over how to make our environments meet our needs.

Solar leaves are still under development, biophotovoltaic moss isn’t generating a commercially viable amount of energy yet, and there’s much more to learn about how to effectively use these mutant roses. But with further evolution along these lines, manmade technology may one day become as sophisticated and efficient as that of the alien organisms we share our planet with.

So, can new technology change the way we garden?

In a word: yes.

But still a mystery are how long we will take to change, and what those shifts in our habits will look like.

The home gardener can take advantage whenever they can afford to. At a larger scale, with industrial farming, there are far more factors to consider. Even with our livelihoods at stake, transformational sustainable agriculture isn’t getting the uptake it needs to significantly improve our chances of survival. The findings and technology are there, but many expensive and interdependent factors can make it difficult to revolutionise standard practice.

Speaking for myself, I can get with placing sensors and automators throughout my garden. This change on a small scale seems within reach, and makes busy-life gardening all the more possible.