“A garden should be just a little too big to keep the whole cultivated. Then it gives it a chance to go a little wild in spots”.

Edna Walling’s charming observation, featured on the back cover of Richard Aitken’s Planting Dreams: Shaping Australian Gardens is a fitting analogy for the scope of this handsome new book, published to coincide with the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney’s 200th birthday celebrations. Not that Aitken’s book focusses particularly on the RBGS. In fact it’s somewhat challenging to pin down the purpose of this intriguing work.

You might describe it as a social history of Australia viewed from the perspective of our relationship with and desire to reshape our physical environment, but Planting Dreams is a much more lively exploration than this description suggests, chiefly because of the beautifully reproduced artefacts that illustrate Aitken’s text. This book looks fabulous. Each chapter is introduced by a stunning double-page graphic. The reproductions featured are crystal clear, and the whole 250 pages of the book are beautifully laid-out and printed on a quality off-white stock. It’s a very elegant production.

You might describe it as a social history of Australia viewed from the perspective of our relationship with and desire to reshape our physical environment, but Planting Dreams is a much more lively exploration than this description suggests, chiefly because of the beautifully reproduced artefacts that illustrate Aitken’s text. This book looks fabulous. Each chapter is introduced by a stunning double-page graphic. The reproductions featured are crystal clear, and the whole 250 pages of the book are beautifully laid-out and printed on a quality off-white stock. It’s a very elegant production.

Chapter 3 Taming the Landscape in ‘Planting Dreams – Shaping the Australian Garden’

Sourced almost exclusively from Sydney’s State Library of New South Wales, Aitken’s eclectic selection of plans, botanical illustrations, magazine covers and etchings, from the 14th century to the 21st, and from Queensland’s Surfer’s Paradise to the Empress Josephine’s Malmaison, is the glue that ties the narrative together. In fact, the artefacts are the real stars of both the book and its companion exhibition, currently running at the State Library and styled – as a friend remarked – after the ‘100 Objects’ approach in current curatorial vogue.

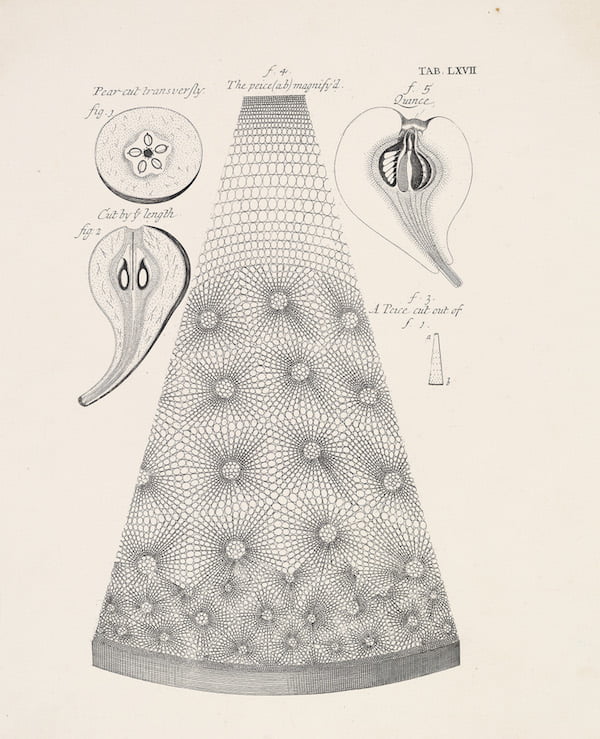

View of a pear, made possible with the invention of the microscope. From Robert Hooke’s Micrographia

How surprising then, that the in-text captioning in the book is so generic that it tends to undermine the significance of the material featured. The inclusion, for example, of what appears to be the cover design for Patrick White’s 1955 novel The Tree of Man, seems rather unremarkable. Turn to the meticulously detailed List of Illustrations appendix at the back of the book however, and you discover that this is actually the artwork commissioned for White’s Nobel Prize for Literature diploma, awarded in 1973! Maybe it’s the history student in me, but I also found the shortage of dates, both in the captions and the accompanying text, exasperating. Neither Aitken’s discussion, nor the following two page spread devoted to stunning engravings from Grew’s The Anatomy of Plants and Robert Hooke’s famous Micrographia, include publication dates for these pioneering works. Once again, a visit to the well-thumbed appendix is required for this information (1682 and 1665, respectively, if you’re wondering).

The microscope, depicted in Robert Hooke’s Micrographia. In ‘Planting Dreams – Shaping Australian Gardens’ p29

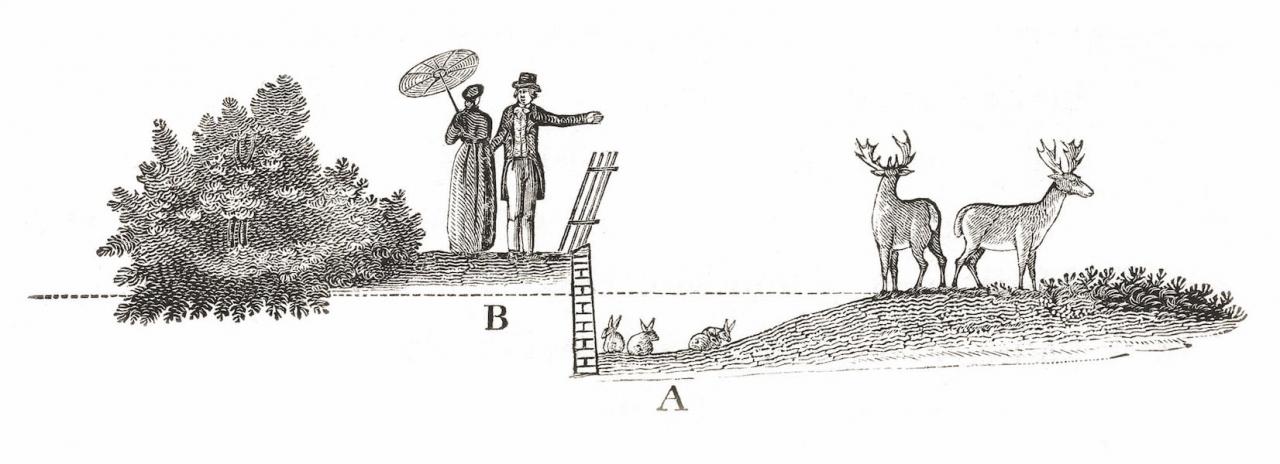

Illustration of Humphrey Repton’s ‘ha ha’ in ‘Planting Dreams – Shaping Australian Gardens’ p33

There is, however, much of interest and tremendous value in this sumptuous production. Humphrey Repton’s 1816 visual explanation of a ‘ha ha’ cleared up my confusion on that subject, while a stylish Wunderlich Durasbestos advertisement from 1940 opened my eyes both to the lost art of poster design and to the role played by asbestos sheet in the emerging DIY building and landscaping market after WWII.

Poster of Wunderlich Durabestos in ‘Planting Dreams – Shaping the Australian Garden’

And who knew that Margaret Flockton was employed by the American Tobacco Company to produce a series of botanical prints which smokers could obtain by trading-in “100 Premium Certificates from … Old Judge Cigarettes”? (“Sic transit gloria mundi”** – as Aitken dryly observes.) This gentle and appealing wryness also pervades his exploration of the circularity of gardening trends in Australia over the past 250 years. The ambivalence that characterises White Australia’s attitude towards the use of indigenous flora in the home garden is a recurrent theme throughout the book, as is the observation that while there have historically been many women who garden, female gardening ‘experts’ have remained disproportionately thin on the ground. As the narrative implies, there really is nothing new under the sun.

New Horizons in ‘Planting Dreams – Shaping the Australian Garden’ Pages 176-177

Perhaps it’s just my personal bias, but I would have preferred less focus on the World Wars in Aitken’s overview. We’re all fairly familiar with enlistment posters and soldiers’ diary, which, I’d argue, are of questionable relevance to the topic of gardens. I would much rather have read more about the ‘garden’ suburb experiments at Daceyville and Haberfield, in which town planning pioneer, John Sulman played a role. Aitken refers fleetingly to these developments but without further textual or visual explanation.

Suburban Idyll in ‘Planting Dreams – Shaping the Australian Garden’ Pages 208-209

Likewise, while the photos used to illustrate the discussion of the 1980s ‘surburban idyll’ are wonderfully evocative, they are only allocated two half pages. A reproduction of Margaret Woodward’s portrait of civil rights activist Faith Bandler is, meanwhile, allotted a full page in the same chapter. It’s a great portrait of an enormously influential figure in Australian history, and obviously an important part of the State Library’s collection, but what does it have to do with Australian gardens? This seems like a case of the tail wagging the dog.

Aitken is a leading garden historian in Australia, and has an obvious affinity for his subject matter. His narrative is the result of wide-ranging and careful research, as the meticulously prepared bibliography and extensive footnotes attest. The generous index is also a welcome (and increasingly rare these days) inclusion. And, as I’ve mentioned previously, this is a visually impressive production.

If you like books that are readily categorisable and singular in purpose, then Planting Dreams: Shaping Australian Gardens is probably not for you. If, however, you’re an inquisitive reader, happy to follow a somewhat meandering narrative thread, you’ll find its eclecticism and thematic ambiguity an irresistible delight. Being more in the former camp than the latter, I was initially frustrated by this book, though with perseverance my allegiances began to shift. While I think Aitken’s text struggles to convincingly harness the State Library’s stunning visual material to his thematic task, it’s still a beautiful, unique and ultimately rewarding book.

Planting Dreams: Shaping Australian Gardens by Richard Aitken

A NewSouth book, AU$49.99

Hardback ISBN 9781742234649

[**“Thus passes the glory of the world.”]